The story of Gulabo, the tribal girl who was buried alive at birth but after being rescued by her aunt, reclaimed her life through the serpent dance. Gulabo or Gulabi has won several international accolades and was recently awarded the Padma Shri, one of the highest civilian awards conferred by the Government of India. He latest international collaboration is with French musician Thierry “Titi” Robin. Here’s her story.

Buried alive at birth, she reclaimed her life back to glory

Minutes after she was born, community elders did to Gulabi what they did to all other female infants—they buried her alive, with her end of the umbilical cord still attached to her belly.

Had her aunt not harrowed the child out of her freshly dug grave at midnight that Dhanteras in November 1972, the world would not have known Sapera dance.

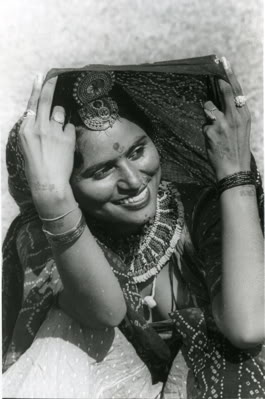

Gulabi Sapera, creator of Rajasthan’s celebrated serpent dance, was awarded the Padma Shri on Tuesday—the only one from her community to be ever bestowed the honour, and the only woman from Rajasthan to figure in the nation’s highest civilian awards in five years.

“I feel more responsible now. The art for which I have been awarded needs to be preserved and promoted,” says the 44 year old, at her modest residence, located in a narrow lane in Jaipur’s Shastri Nagar.

Her real name is Dhanvanti, as she was born on the festive day of Dhanteras. When she was 1, she fell seriously ill and was taken to a peer who placed a rose on her chest,.

“I had almost died. So when I came back to life with the blessing of the rose, my father said Dhanvanti is dead now and Gulabi is born,” she says.

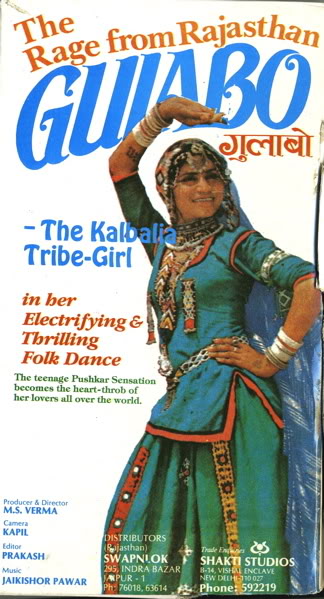

The name Gulabo, by which she is popularly known as, is the result of a typo in magazine Dharmayug, she claims.

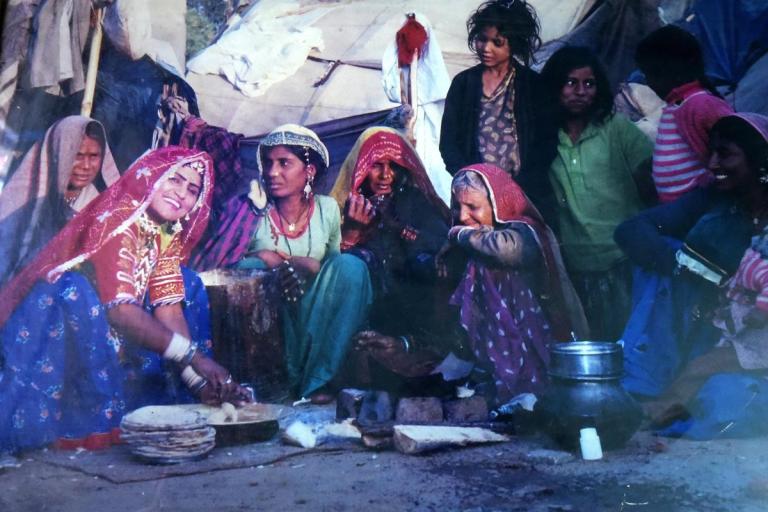

The Sapera community, traditionally engaged in catching and “charming” serpents, didn’t want to be burdened with looking after a girl child in their open, jungle encampments, and would kill a daughter as soon as she was born, says Gulabi.

“But my father didn’t like the practice. Ours was one of the very few homes that had three girls, all born before me. I was the 7th child. The elders managed to bury me since my father was not home the day I was born.”

“For another couple of years, fearing I would be killed if left at home, my father would carry me around in one of his straw snake baskets. He would also feed me leftover milk meant for the snakes,” she recalls her father later telling her.

Dancing professionally, was unheard of in the Sapera community, but that didn’t stop two year old Gulabo to sway along with her father’s serpents on the tunes of the Been.

In 1985, she recalls dancing on the sand along with her friends at the Pushkar fair, when she was spotted by Rajasthan tourism department officials Tripti Pandey (sister of Ila Arun) and Himmat Singh. The duo were apparently charmed by “this little girl who moves as if there were no bones in her body”.

Later that day Tripti and Himmat convinced her father to allow 13 year old Gulabi to dance on a stage for the first time.

“I had only danced on bare ground till then at Holi and those watching would throw coins at us. This audience did not throw coins, but applauded and appreciated my art. I felt like I was dancing in a temple,” she recalls.

The now famous wild, whirling dance moves synonymous with Sapera dance, came about organically from watching snakes move about to her father’s Been.

Her trademark black dress, adorned with tiny mirror embellishments and cotton thread braids, was inspired from the celluloid.

At seven, she watched the film “Asha” and was smitten by the dress worn by Reena Roy in her iconic song “Sheesha ho ya dil ho”.

“I immediately knew that I wanted that dress and had it stitched. Later, when I danced on the stage, I wore it and since then it has almost become my sceond skin,” she says.

After Pushkar, Gulabo knew she had to be a dancer. “My life was meant to be different. I couldn’t stay back in my village and continue to beg for alms,” she says.

Later that year, Gulabi was noticed by noted art curator and scenographer Rajiv Sethi in Delhi, who drew the then PM Rajiv Gandhi’s attention to her. That led to the young desert danseuse traveling to Washington to perform at the “Festival of India”.

When she returned, the same community elders who had buried her alive after birth and later boycotted her family, welcomed her back into the community and elected her the president of the caste association.

“I accepted it only after making them pledge that they would stop killing their daughters. They agreed, saying they wanted a Gulabo to be born in their homes and bring them glory,” says Gulabo.

Having performed her Sapera dance in over “165 countries with the exception of Pakistan”, Gulabo has lately been collaborating with French composer Thierry “Titi” Robin.

The duo released a 14 track album “Rakhi” in 2002, featuring a fusion of Robin’s mediterranean musical environment with Rajasthan’s rusty gypsy sounds performed by Gulabo.

“I dont like the term Kalbeliya dance. I called it Sapera dance because it was inspired by movements of snakes. Kalbeliya is a negative term, it means friends of death. Since saperas would catch snakes and live with them and snakes were equated with Kaal or death at that time, people called them Kalbeiyas,” she says about her music.

At 44, despite being a grandmother, Gulabo’s feet continue to move at the desert’s gypsy tunes.

“You are only as old as you feel. I can still dance for hours. In fact, toursim officials always worry that I won’t stop dancing and ruin their schedule. When i start dancing, I feel possessed by some power and once it starts, it takes me higher and higher”.

The longest she has danced is for eight straight hours on the sand dunes of Jaisalmer.

“I don’t feel any competition from younger dancers. I created this form. I love it when I see young girls dancing to Sapera tunes. There is no college festival in Rajasthan where the dance is not performed. Gulabo will always be alive in these college performances,” she says.

Despite having created the dance form, she doesn’t feel the need to get it copyrighted in her name.

“I believe in keeping it free. Because I don’t own it. It was given to me by god to spread it. It is owned by god.

Sapera dance has no calculated steps like Kathak etc. It is wild and free. It has a begining but no end. It just goes on and on and on,” says Gulabo.